Most of everything we know about the giant squid (Architeuthis sp.) has

come from the examination of animals that have either been washed up on

beaches, spit up by sperm whales or caught accidentally in large fishing

trawls. Because of the relative rarity of well preserved specimens,

whenever one is

found,

there is an opportunity

to learn something new about this elusive creature.

Most of everything we know about the giant squid (Architeuthis sp.) has

come from the examination of animals that have either been washed up on

beaches, spit up by sperm whales or caught accidentally in large fishing

trawls. Because of the relative rarity of well preserved specimens,

whenever one is

found,

there is an opportunity

to learn something new about this elusive creature.

Recently, a number of giant squid have been caught in the large,

deep-water fishing trawls in the waters around New Zealand and

Australia. One in particular, caught just a few weeks ago in the

waters just south of Kaikoura Canyon, was recovered in excellent

condition and was awaiting Clyde's arrival, safely stored in a large,

walk-in freezer here at the NIWA lab.

Every so often, a large refrigerated truck pulls up to Steve O'Shea's

back door and deposits a large bag or box containing the frozen remains

of some sea creature that has been found. In addition to his job as

curator of the collection of marine organisms, Steve is also the guy

that most fisherman know is the person who wants any giant squid that

may accidentally get caught in one of their trawl nets. Some fishing

boats have observers on deck who quickly bag and freeze any squid that

may come on board - not an easy task when you are faced with a 200

kilogram or more mass of very unresponsive squid on the heaving deck of

a working fishing boat.

Every so often, a large refrigerated truck pulls up to Steve O'Shea's

back door and deposits a large bag or box containing the frozen remains

of some sea creature that has been found. In addition to his job as

curator of the collection of marine organisms, Steve is also the guy

that most fisherman know is the person who wants any giant squid that

may accidentally get caught in one of their trawl nets. Some fishing

boats have observers on deck who quickly bag and freeze any squid that

may come on board - not an easy task when you are faced with a 200

kilogram or more mass of very unresponsive squid on the heaving deck of

a working fishing boat.

The markings on the outside of the bags are often a wonder of

understatement. This particular specimen came wrapped in a very large

brown sack with the words "Giant Squid, Museum Wellington" scrawled

across the outside. For the past few days, this bag has been sitting

on one of the large dissection tables at the NIWA lab, thawing

gradually, awaiting today's activities.

The markings on the outside of the bags are often a wonder of

understatement. This particular specimen came wrapped in a very large

brown sack with the words "Giant Squid, Museum Wellington" scrawled

across the outside. For the past few days, this bag has been sitting

on one of the large dissection tables at the NIWA lab, thawing

gradually, awaiting today's activities.

Last night, Clyde and Steve

went through many of the published reports of giant squid observations

in an effort to come up with a list of all the key measurements that

Clyde and Mike would be making the next day.

This list filled several pages of Clyde's bright red notebook. Some of the

measurements

like Mantle Length, Mantle Width, and Arm Length are

fairly obvious. Ones like the thickness of the mantle, or the

circumference of each arm at the base were a little less obvious (to me

at least) and a little more difficult to actually make as you shall

see.

Last night, Clyde and Steve

went through many of the published reports of giant squid observations

in an effort to come up with a list of all the key measurements that

Clyde and Mike would be making the next day.

This list filled several pages of Clyde's bright red notebook. Some of the

measurements

like Mantle Length, Mantle Width, and Arm Length are

fairly obvious. Ones like the thickness of the mantle, or the

circumference of each arm at the base were a little less obvious (to me

at least) and a little more difficult to actually make as you shall

see.

Making sure that they had everything, Mike and Clyde

wheeled the cart

containing all the cameras, dissecting tools and waterproof clothing

(boots, gloves and aprons) along the path by Evans Bay to the lab where

the squid was thawing. The first thing that they needed to do after

making sure that the squid was defrosted enough to easily reposition

without doing any damage to it, was to gently

unfold the squid and

begin to arrange it

in a more "natural"

position. In order to fit into

the ship's freezer, the squid's arms had been folded back along the

mantle, bending the head in the process. With great care, they were

able to extend the arms until the squid very nearly filled the entire

length of the dissection table.

Making sure that they had everything, Mike and Clyde

wheeled the cart

containing all the cameras, dissecting tools and waterproof clothing

(boots, gloves and aprons) along the path by Evans Bay to the lab where

the squid was thawing. The first thing that they needed to do after

making sure that the squid was defrosted enough to easily reposition

without doing any damage to it, was to gently

unfold the squid and

begin to arrange it

in a more "natural"

position. In order to fit into

the ship's freezer, the squid's arms had been folded back along the

mantle, bending the head in the process. With great care, they were

able to extend the arms until the squid very nearly filled the entire

length of the dissection table.

Based on this specimen, there is no doubt that giant squid contain the

dark, sepia-colored ink that we associate with the smaller, more

familiar squid. The entire squid, and very soon all of us were covered

with it. Clyde took a hose and very carefully

washed the entire squid

from head to toe (oops, I meant arms to tail). In the process, Clyde

gave me a quick lesson in giant squid anatomy pointing out such

features at the large, parrot-like

beak at the

base of the 8 arms, and the two, very large

gills

resting inside the mantle cavity.

Based on this specimen, there is no doubt that giant squid contain the

dark, sepia-colored ink that we associate with the smaller, more

familiar squid. The entire squid, and very soon all of us were covered

with it. Clyde took a hose and very carefully

washed the entire squid

from head to toe (oops, I meant arms to tail). In the process, Clyde

gave me a quick lesson in giant squid anatomy pointing out such

features at the large, parrot-like

beak at the

base of the 8 arms, and the two, very large

gills

resting inside the mantle cavity.

Once the squid had been thoroughly cleaned and arranged, the work of

making the

measurements began.

Using a long piece of string and a

measuring board, Mike and Clyde measured widths, lengths, diameters,

circumferences and thicknesses of many things that I had never heard of

in my life. Thankfully, Ingrid understood and stood by with the red notebook,

calling out the next measurement that needed to be made and then

carefully recording the number that was given to her, and repeating it

for confirmation.

Once the squid had been thoroughly cleaned and arranged, the work of

making the

measurements began.

Using a long piece of string and a

measuring board, Mike and Clyde measured widths, lengths, diameters,

circumferences and thicknesses of many things that I had never heard of

in my life. Thankfully, Ingrid understood and stood by with the red notebook,

calling out the next measurement that needed to be made and then

carefully recording the number that was given to her, and repeating it

for confirmation.

I guess the word had gotten out about the giant squid that was being

examined today, because all during the day, large numbers of

curious visitors,

many of them affiliated with NIWA in one way or another,

cautiously stepped into the lab and asked if they could have a look at

this creature whom most had only ever read about, but never seen. It

was a rather surreal scene watching Mike and Clyde going about their

often grisly work while people posed for pictures in the background.

At one point,

Steve's wife and parents

came in to visit both with Steve AND the

squid.

I guess the word had gotten out about the giant squid that was being

examined today, because all during the day, large numbers of

curious visitors,

many of them affiliated with NIWA in one way or another,

cautiously stepped into the lab and asked if they could have a look at

this creature whom most had only ever read about, but never seen. It

was a rather surreal scene watching Mike and Clyde going about their

often grisly work while people posed for pictures in the background.

At one point,

Steve's wife and parents

came in to visit both with Steve AND the

squid.

Through the morning and into the late afternoon the

measuring,

counting

and sampling continued until finally, everything that needed to be

measured, counted or sampled, had been. Because this particular

specimen, which according to Clyde was the most perfectly intact one

that he had ever worked on with only the two long feeding tentacles

missing, was destined for display in a museum, it needed to be

preserved until it could be put on display. Since there are not too many

little glass jars

that could contain something this big, Steve

spent about an hour injecting over 5 liters of formalin into it with a

large syringe before moving it later in the evening into a large,

coffin-like metal box filled with the preservative.

Through the morning and into the late afternoon the

measuring,

counting

and sampling continued until finally, everything that needed to be

measured, counted or sampled, had been. Because this particular

specimen, which according to Clyde was the most perfectly intact one

that he had ever worked on with only the two long feeding tentacles

missing, was destined for display in a museum, it needed to be

preserved until it could be put on display. Since there are not too many

little glass jars

that could contain something this big, Steve

spent about an hour injecting over 5 liters of formalin into it with a

large syringe before moving it later in the evening into a large,

coffin-like metal box filled with the preservative.

However, one of

the things that most of us commented on during the day was how

relatively clean and fresh the squid actually smelled. Half expecting

to be overwhelmed by the smell of either rotting flesh or of ammonia as

was described in some of the giant squid literature, it was almost like

being in a well maintained fish market.

However, one of

the things that most of us commented on during the day was how

relatively clean and fresh the squid actually smelled. Half expecting

to be overwhelmed by the smell of either rotting flesh or of ammonia as

was described in some of the giant squid literature, it was almost like

being in a well maintained fish market.

Clyde, never being one to miss an opportunity to make a point in the

most dramatic way possible, quite visibly

demonstrated how pleasant

smelling the squid actually was. Although he vowed that he would

regret it later, I was able to convince Clyde to provide a

representative sense of scale for the giant squid by climbing up on the

table and letting me take a picture of man and beast. However, the

only way that I was able to do that was by climbing up there and doing it

first.

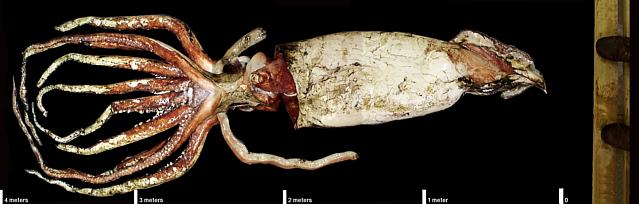

Since most squids are rarely in this incredibly good condition,

everyone thought that it should really be photographed before going

into the bath of formalin. Looking around the lab to see what we had

to work with, I found two ladders and a couple of boards. Building a

makeshift scaffold that straddled the dissecting table, I climbed up

the ladder, walked out onto the boards (while Clyde and Mike both held

onto the base of the ladders and looked on in slight disbelief) and

with my head braced against the ceiling, took a picture as close to

vertical that I could. We then moved the ladder a few feet further

down the table and the process was repeated. The picture below is one

of the first, full color composites of a giant squid taken from

straight above rather than at the rather low oblique angle that often

appears in the literature.

Since most squids are rarely in this incredibly good condition,

everyone thought that it should really be photographed before going

into the bath of formalin. Looking around the lab to see what we had

to work with, I found two ladders and a couple of boards. Building a

makeshift scaffold that straddled the dissecting table, I climbed up

the ladder, walked out onto the boards (while Clyde and Mike both held

onto the base of the ladders and looked on in slight disbelief) and

with my head braced against the ceiling, took a picture as close to

vertical that I could. We then moved the ladder a few feet further

down the table and the process was repeated. The picture below is one

of the first, full color composites of a giant squid taken from

straight above rather than at the rather low oblique angle that often

appears in the literature.

Regardless, with good humor, great strength and incredible care, the

squid was

gently lifted

off the dissecting table so that a large blue

plastic tarp could be placed beneath it. Like two anxious parents,

both Clyde and Steve were

on the table

with the squid, orchestrating

each maneuver so as not to damage any of the squid's rather delicate

parts. With great coordination, the squid was finally

lifted off the table with a collective grunt

from all participants. It was my good

fortune to have the job of photographer so I got to stand off in the

distance rather than risk embarrassing myself and demonstrate my lack of

strength.

Formalin is a very nasty chemical and not one to be treated lightly.

Careful to minimize anybody's exposure to the fumes (the

children were not allowed anywhere near the room in which it was kept)

Steve and Clyde gave all the folks very careful instructions as to what

to do, what not to touch and made sure that things went as smoothly and

as QUICKLY as possible.

Every so often, a large refrigerated truck pulls up to Steve O'Shea's

back door and deposits a large bag or box containing the frozen remains

of some sea creature that has been found. In addition to his job as

curator of the collection of marine organisms, Steve is also the guy

that most fisherman know is the person who wants any giant squid that

may accidentally get caught in one of their trawl nets. Some fishing

boats have observers on deck who quickly bag and freeze any squid that

may come on board - not an easy task when you are faced with a 200

kilogram or more mass of very unresponsive squid on the heaving deck of

a working fishing boat.

Every so often, a large refrigerated truck pulls up to Steve O'Shea's

back door and deposits a large bag or box containing the frozen remains

of some sea creature that has been found. In addition to his job as

curator of the collection of marine organisms, Steve is also the guy

that most fisherman know is the person who wants any giant squid that

may accidentally get caught in one of their trawl nets. Some fishing

boats have observers on deck who quickly bag and freeze any squid that

may come on board - not an easy task when you are faced with a 200

kilogram or more mass of very unresponsive squid on the heaving deck of

a working fishing boat.

Most of everything we know about the giant squid (Architeuthis sp.) has

come from the examination of animals that have either been washed up on

beaches, spit up by sperm whales or caught accidentally in large fishing

trawls. Because of the relative rarity of well preserved specimens,

whenever one is

found,

there is an opportunity

to learn something new about this elusive creature.

Most of everything we know about the giant squid (Architeuthis sp.) has

come from the examination of animals that have either been washed up on

beaches, spit up by sperm whales or caught accidentally in large fishing

trawls. Because of the relative rarity of well preserved specimens,

whenever one is

found,

there is an opportunity

to learn something new about this elusive creature.