![]() Back in December, I received one of the American Teacher Awards from Disney

and McDonald's Corporations. There was a party for me at a local

McDonald's restaurant. At the party, Jane Strauss, one of the members of

our local school board, spoke at length with Ingrid Roper, Clyde's wife.

Back in December, I received one of the American Teacher Awards from Disney

and McDonald's Corporations. There was a party for me at a local

McDonald's restaurant. At the party, Jane Strauss, one of the members of

our local school board, spoke at length with Ingrid Roper, Clyde's wife.

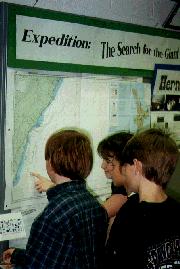

She also toured the school and my classroom where we were setting up the

Giant Squid Expedition Herndon Outpost. I explained our problem with

getting e-mail and Internet access. Ms. Strauss became very excited about

the project and promised to do what she could to make our dream a reality.

Within three days, we were hooked up to the Internet.

However, Clyde, Ingrid, and the expedition team had left for

Kaikoura. They took with them my home e-mail address in hopes

that I could relay journals and messages to the class.

She also toured the school and my classroom where we were setting up the

Giant Squid Expedition Herndon Outpost. I explained our problem with

getting e-mail and Internet access. Ms. Strauss became very excited about

the project and promised to do what she could to make our dream a reality.

Within three days, we were hooked up to the Internet.

However, Clyde, Ingrid, and the expedition team had left for

Kaikoura. They took with them my home e-mail address in hopes

that I could relay journals and messages to the class.

February arrived and we were ready to hear from the expedition. We brought the In Search of Giant Squid Web Page up each day on the classroom computer to see if anything had been posted. I raced to my own computer each evening after putting my kids to bed to see if there were any messages. Nothing. Clyde had mentioned his itinerary would involve a couple of weeks of checking equipment and gathering the team, so we weren't too worried.

![]() In the meantime, we wrote letters of encouragement and made drawings of the

research team studying the sperm whales and giant squid.

We sent this first batch to the marine laboratory at Edward Percival Research Station on

Kaikoura Peninsula.

In the meantime, we wrote letters of encouragement and made drawings of the

research team studying the sperm whales and giant squid.

We sent this first batch to the marine laboratory at Edward Percival Research Station on

Kaikoura Peninsula.

The students drew cartoons with giant squid

characters, scenes of sperm whales eating giant squid, and scenes of

Clyde's team in action. I told them that a large part of the expedition

would be to monitor equipment and wait.

The students drew cartoons with giant squid

characters, scenes of sperm whales eating giant squid, and scenes of

Clyde's team in action. I told them that a large part of the expedition

would be to monitor equipment and wait.

When the first e-mail from Clyde came we couldn't wait to read it. I

photocopied it for the whole team, along with Clyde and Ingrid's vivid

journals of their adventures thus far. We were ravenous for news.

"Did he find the giant squid?" rang through the halls of our

middle school. I smiled, shook my head no, and handed them the

e-mail message.

It had to be translated. It was classic Clyde,

full of good New England humor, "advanced scientific" terminology ("We

saw a ..... whizz-by"), updates on their boats, Tanekaha and the

Mystique, the automated underwater vehicle, the Odyssey, and

details of their preparations. It was fascinating.

It had to be translated. It was classic Clyde,

full of good New England humor, "advanced scientific" terminology ("We

saw a ..... whizz-by"), updates on their boats, Tanekaha and the

Mystique, the automated underwater vehicle, the Odyssey, and

details of their preparations. It was fascinating.

The students were learning firsthand, almost as if they were there,

about:

The students were learning firsthand, almost as if they were there,

about:

No textbook could do this, although I'd like to

see the journals and e-mail messages in a textbook one day. This was

real and happening right now. The expedition was accessible. The

students sensed they were a part of history.

I decided then to make Ingrid's journals the source material for

our study of parts of speech and summarization. From then on, we printed Ingrid's journals and Clyde's e-mail messages.

Ingrid's journals were beautifully written, worthy of National Geographic

or Smithsonian publications.

I decided then to make Ingrid's journals the source material for

our study of parts of speech and summarization. From then on, we printed Ingrid's journals and Clyde's e-mail messages.

Ingrid's journals were beautifully written, worthy of National Geographic

or Smithsonian publications.

I never knew this wordsmith side of her. She

seemed to genuinely enjoy the writing as well, which was a wonderful model

for my students.

Clyde later wrote e-mail messages directly to our team, often inserting

teachable moments ("Think about your answer to that question I just asked

before reading futher for the answer"). He asked us to look up words he was

using. He responded to specific students by name (from their own e-mail).

He told us how much our letters and support meant to his team, and he

encouraged student studies. He also reminded us that there was more to

life than giant squid.

Clyde later wrote e-mail messages directly to our team, often inserting

teachable moments ("Think about your answer to that question I just asked

before reading futher for the answer"). He asked us to look up words he was

using. He responded to specific students by name (from their own e-mail).

He told us how much our letters and support meant to his team, and he

encouraged student studies. He also reminded us that there was more to

life than giant squid.

They say that education only occurs when there is conflict. If that's the case, we learned a tremendous amount on the day we received an e-mail from Clyde explaining what happened with the crittercam operation and with the beached sperm whales.

Clyde explained that the weather had been unusually windy and cold for

summer in New Zealand (They are in the Southern Hemisphere - seasonal

temperatures and moisture are the opposite for those in the Northern

Hemisphere).

Clyde explained that the weather had been unusually windy and cold for

summer in New Zealand (They are in the Southern Hemisphere - seasonal

temperatures and moisture are the opposite for those in the Northern

Hemisphere).

![]() He explained that animal rights groups had protested their

efforts to attach the crittercams to the tops of sperm whales. The suction

cups weren't enough, however, for the wrinkled and moving skin - tiny hooks

were used to "grab" the upper epidermis. The protesters thought this was

abusive. Eventually, the expedition team received a 15-month permit to

use the suction cups to attach the cameras to the whales.

He explained that animal rights groups had protested their

efforts to attach the crittercams to the tops of sperm whales. The suction

cups weren't enough, however, for the wrinkled and moving skin - tiny hooks

were used to "grab" the upper epidermis. The protesters thought this was

abusive. Eventually, the expedition team received a 15-month permit to

use the suction cups to attach the cameras to the whales.

The class debated the merits of obtaining scientific knowledge at the possible expense of pain to an animal or testing subject. We felt pretty sure the whales wouldn't feel the tiny hooks, but debated as if the whales could feel a bit of pain -- Which is the greater priority: discovery or comfort of animals?

The second controversy was even more stirring. Clyde wrote to us of five

beached sperm whales found along the shore. The scene moved him deeply.

We gathered around the computer

and viewed the multiple images of those whales available on the

Kaikoura module on the National Geographic website. The students were silent at

first, listening to Clyde's words. They saw the haunting images of the

huge carcasses, mouths agape in a final struggle against gravity, and Clyde

and Malcolm standing next to them on the misty shoreline.

The second controversy was even more stirring. Clyde wrote to us of five

beached sperm whales found along the shore. The scene moved him deeply.

We gathered around the computer

and viewed the multiple images of those whales available on the

Kaikoura module on the National Geographic website. The students were silent at

first, listening to Clyde's words. They saw the haunting images of the

huge carcasses, mouths agape in a final struggle against gravity, and Clyde

and Malcolm standing next to them on the misty shoreline.

The controversy was over animal euthanasia. Moments before, Clyde and the

bioacoustical team heard that two of the whales were still alive. They

raced to the beached whales to obtain a few minutes of recordings of the

whale signals. Evidently, sperm whale recordings are very rare.

While they pleaded their case to

get their recordings, they heard the rifle shots that killed the final two

whales. The officials put the two creatures out of their misery. No one

spoke as I read the e-mail describing those moments. I also shared Tom

Allen's observations from the National Geographic dispatches.

The controversy was over animal euthanasia. Moments before, Clyde and the

bioacoustical team heard that two of the whales were still alive. They

raced to the beached whales to obtain a few minutes of recordings of the

whale signals. Evidently, sperm whale recordings are very rare.

While they pleaded their case to

get their recordings, they heard the rifle shots that killed the final two

whales. The officials put the two creatures out of their misery. No one

spoke as I read the e-mail describing those moments. I also shared Tom

Allen's observations from the National Geographic dispatches.

![]() Clyde and his team were allowed to examine the whales' bodies afterwards.

They found repeated evidence of encounters with giant squid and other types

of squid. Clearly defined sucker marks were scattered across whale skin.

Many of them had healed quickly due to the saltwater, Clyde explained on

the dispatch.

Clyde and his team were allowed to examine the whales' bodies afterwards.

They found repeated evidence of encounters with giant squid and other types

of squid. Clearly defined sucker marks were scattered across whale skin.

Many of them had healed quickly due to the saltwater, Clyde explained on

the dispatch.

There was a third setback. Earlier, it become clear that the automated

Odyssey had limitations maneuvering in the rocky

and uncertain terrain of the underwater canyon. Between this, the beached

whales and the crittercam issues, it seemed to the students as if

the expedition team kept getting close to finally encountering the giant

squid, only to have "the rug pulled out from under them," forcing another

long wait. We learned a new word that day: "elusive". The images of the

sucker welts were exciting, however. We knew the expedition was in the

right area.

![]()

Smithsonian Giant Squid Overview Page

gene carl feldman / gene@seawifs.gsfc.nasa.gov